This activity is provided by Med Learning Group.

This activity is supported by an educational grant from Lilly.

Copyright © 2024 Med Learning Group. Built by Divigner. All Rights Reserved.

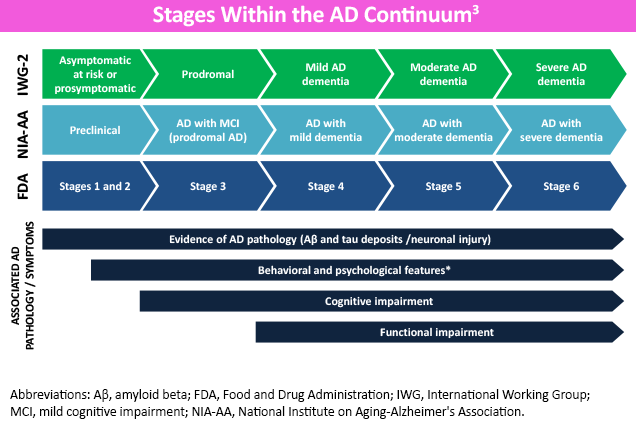

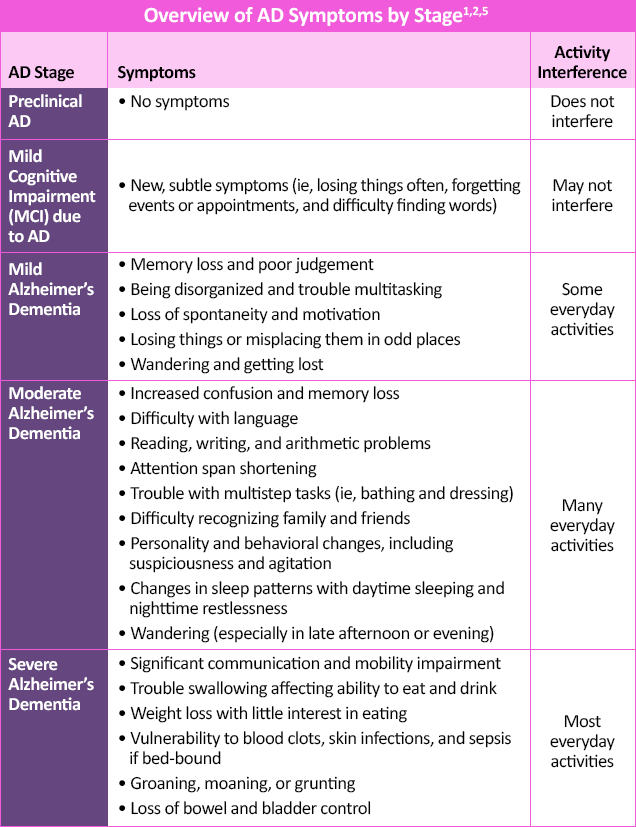

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative condition, characterized by the accumulation of extra-neuron beta-amyloid protein (plaques) and intra-neuron tau protein (tangles) in the brain.1 The stages of AD are classified by degree of cognitive impairment, ranging from no AD symptoms in the preclinical form to severe symptoms in later stages.1,2

One of the earliest and most common symptoms of AD is memory loss, specifically “recent” memory impairment with relative sparing of long-term memory.2,4 Patients with AD may eventually develop difficulties with problem-solving, judgment, organization and executive function, and subsequently impaired multitasking and abstract thinking.2 With disease progression arises the inability to complete tasks and reduced insight, potentially impacting capability to safely perform activities like driving.4

In later stages, language disorders and trouble with visuospatial skills arise.2 Moderate-to-late stages of AD may also demonstrate neuropsychiatric symptoms of apathy, lack of inhibition, psychosis, agitation, social withdrawal, and wandering, and is associated with a more rapid decline if present early.2,4 In end-stage AD, difficulties with verbal communication and movement can result in being bed-bound and incontinent, with total dependence on caregivers.1,2

Since AD generally worsens over time, early diagnosis benefits both the patients and their caregivers.2 It allows them to address modifiable risk factors that may delay cognitive decline, start treatment or enroll in clinical trials before severe stages have set in, and potentially preserve daily functioning for longer.1 Early diagnosis of AD also gives patients and caregivers additional time to learn how to manage behavioral symptoms, discuss future planning and personal/financial issues, address safety concerns, and establish a support network.1

The diagnosis of AD starts by obtaining an accurate history, especially from family members and caregivers.2 A complete physical exam, including neurologic findings, helps rule out other potential causes of dementia.2 Recent studies suggest that anosmia may be an early marker of AD, but more research is needed and this is not a widely used diagnostic finding.6

Detailed cognitive, neurologic, and psychological evaluation can provide a great deal of information about preservation or loss of independent function, as well as presence/types of neuropsychiatric symptoms.4 Mental status exams, especially those evaluating concentration, attention, memory, language, praxis, and visuospatial and executive functioning, can help document the presence and stage of dementia.2,4 Furthermore, formal neuropsychological testing and cognitive assessments can not only establish a dementia baseline, but also help distinguish among other forms of dementia (pseudodementia, Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration) as well as assess competencies for performing potentially dangerous tasks.4 Neuropsychological testing is also the most reliable method for detecting MCI.2 Click here to view and download a cognitive assessment toolkit provided by the Alzheimer’s Association®.

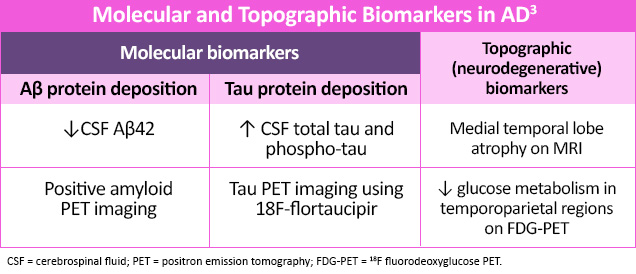

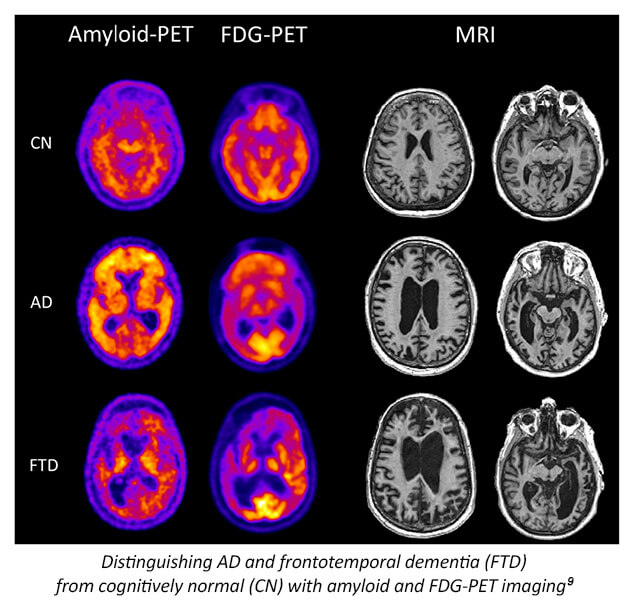

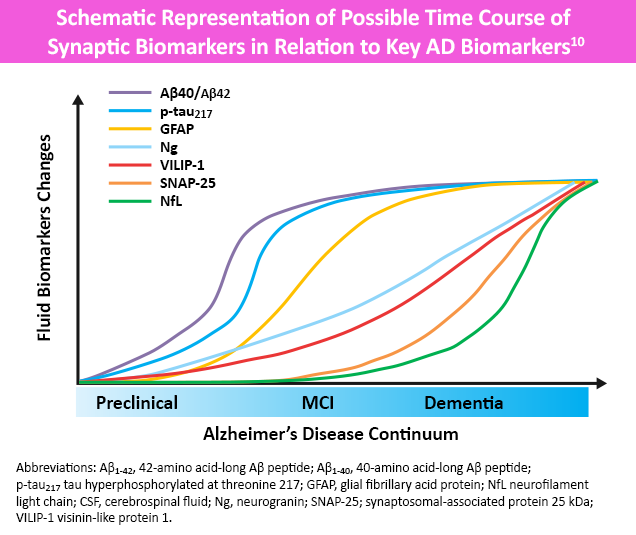

While not yet recommended for routine diagnostic use, several serologic, plasma and advanced imaging biomarkers are being researched to help support an AD diagnosis.4,7 Molecular biomarkers identify specific protein deposits in the brain, like amyloid found in amyloid plaques or tau proteins found in neurofibrillary tangles.4 Topographic (neurodegenerative) biomarkers help locate regional pathologic brain changes associated with AD.3 Neuroimaging, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional brain imaging (eg, amyloid/tau PET and single-photon emission computed tomography [SPECT]) may also help rule out other potential causes of dementia.2,4 More recently, focus has switched to pTau217, i.e. tau phosphorylated at amino acid 217, as this biomarker has consistently shown high performance in differentiating AD from other neurodegenerative disorders and in detecting AD pathology in patients with MCI.8

The most common comorbidities for AD are type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, and inflammatory bowel disease. A key factor in these common chronic diseases is the presence of inflammation. Research is ongoing as to whether inflammation is a cause or effect of AD; likely, it has a bidirectional influence on this neurodegenerative disorder.

Regardless, the presence of these comorbidities noticed in AD patients may have significant implications for the treatment and prognosis of AD. For instance, both diabetes and depression are associated with a worse prognosis in people with AD. Similarly, certain lifestyle factors, like diet and exercise, may also have an impact on cognitive function.

All URLs accessed on February 14, 2024

This activity is provided by Med Learning Group.

This activity is supported by an educational grant from Lilly.

Copyright © 2024 Med Learning Group. Built by Divigner. All Rights Reserved.

Esta actividad es proporcionada por Med Learning Group. Esta actividad es co-proporcionada por Ultimate Medical Academy / Complete Conference Management (CCM).

Esta actividad está respaldada por una beca de educación médica independiente de Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Copyright © 2019 Med Learning Group. Construido por Divigner. Reservados todos los derechos.

Chief Medical Officer

Frank C. and Lynn Scaduto MIND Institute and Behavioral Health

Miami Jewish Health

Miami, FL

Associate Dean of Alzheimer’s Disease Research

Indiana University Distinguished Professor

Barbara and Peer Baekgaard Professor of Alzheimer's Disease Research

Professor in Neurology, Radiology, Medical and Molecular Genetics

Indiana University School of Medicine

Department of Neurology

Indianapolis, IN

Chief Medical Officer, Banner Research

Banner Alzheimer’s and Research Institutes

Pheonix, Sun City, and Tucson, AZ

Director, Banner Sun Health Research Institute

Sun City, AZ

Program Director, AdventHealth Geriatric Fellowship

Winter Park, FL

Director, Massachusetts General Hospital

Frontotemporal Disorders Unit

Professor of Neurology, Harvard Medical School

Boston, MA

Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior

Sidney Kimmel Medical College

Co-Director, Comprehensive Alzheimer’s Center

Vickie & Jack Farber Institute for Neuroscience

Thomas Jefferson University

Philadelphia, PA

Clinical Professor of Medicine

Tufts University School of Medicine

Clinical professor, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Tufts University

Chief, Geriatrics Service, Tufts Medical Center

Senior Physician, Pratt Diagnostic Center

Dean ex officio, Office of International Affairs, Tufts University School of Medicine

Boston, MA

Professor of Neurology

University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

Miami, FL

Professor and Director

Division of Memory Disorders and Behavioral Neurology

Department of Neurology

Heersink School of Medicine

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Birmingham, AL

Henry & Amelia Nasrallah Endowed Professor

Director of Geriatric Psychiatry

Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, MO

Director of Geriatric Cognitive Health

Pacific Neuroscience Institute

Santa Monica, CA

Adjunct Professor

USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology

Los Angeles, CA

President, Kerwin Medical Center

Chief, Geriatric Medicine, Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital

Dallas, TX

Assistant Professor

UT Southwestern Neurology

Dallas, TX

Director, CurePSP Center of Care for PSP, CBD, and MSA

Assistant Professor of Neurology

Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Disease Centers

Baylor College of Medicine

Houston, TX

Founding Director Ray Dolby Brain Health Center

San Francisco, CA

Assistant Professor of Neurology, Harvard Medical School

Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment

Brigham and Women's Hospital

Frontotemporal Disorders Unit

Massachusetts General Hospital

Boston, MA

Director, Division of Geriatrics

Co-director, Center for Memory Loss and Brain Health

Hackensack University Medical Center

Hackensack, NJ

The Saunders Family Chair and Professor of Neurology

Director of the Center for Molecular Integrative Neuroresilience,

Professor of Psychiatry and Neuroscience

Professor of Geriatrics and Adult Development

Department of Neurology and Friedman Brain Institute

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

New York, NY

Chief Medical Officer

Advocate Good Samaritan Hospital

Downers Grove, IL

Moreno Family Chair for Alzheimer’s Research

Vice Chairman for Research and Professor

Department of Neurology

Barrow Neurological Institute

Phoenix, AZ

Rick McCord Professor in Neurology

Umphrey Family Professor of Neurodegenerative Diseases

Director, Neurocognitive Disorders Center

Director, Neurocognitive Disorders Fellowship

McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston

Houston, TX

Professor of Family and Community Medicine

Sidney Kimmel Medical College

Thomas Jefferson University

Philadelphia, PA

Professor of Neurology

Director of the Memory Disorders Program

Georgetown University

Washington, DC

Health Sciences Clinical Professor

UC Irvine Department of Family Medicine

Director, UCI Program in Medical Education for the Latino Community

University of California Irvine

Irvine, CA

John R. Ellis Distinguished Chair of Pharmacy Practice

Professor of Clinical Sciences

Director, Drake Drug Information Center

Drake University College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences

Internal Medicine Clinical Pharmacist

Iowa Methodist Medical Center

Des Moines, IA

Professor of Neurology

Director, Penn Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, PA